Opinion Article

Abstract:

Stepping up ecosystem restoration is critical to achieving pressing policy targets, but as well as significant benefits, there are also multiple challenges particularly associated with restoring at landscape scale. These relate to the complexity of ecosystems, land uses, and social factors within a landscape and the scale at which sustainable funding and effective monitoring are required. Here we present a summary of discussions from a symposium at the Society for Ecological Restoration—Europe conference, addressing five key topics related to scaling up restoration in Europe: implementation, stakeholder engagement, local economies, financing, and monitoring. Common barriers include inflexible political systems and traditional conservation project thinking, as well as the complexities and time required to work effectively and sustainably across disciplines, sectors, and geographical boundaries. However, opportunities are identified in relation to innovative financing systems and monitoring technologies, the development of nature-based economies, and the strength and sustainability that comes from effectively and deeply engaging a wide diversity of stakeholders. Capitalizing on these prospects could enable landscape-scale ecosystem restoration to play a significant role in meeting global targets for nature, climate, and people.

Implications for Practice

- Landscape-scale ecosystem restoration increasingly requires significant time and planning resources. Funding and management frameworks must become more flexible to reflect stakeholder complexity and long-term timelines.

- Alignment from the top-down (policy levers and incentives) and bottom-up (communities and local organizations and institutions) can enable landscape-scale working.

- The creation of a Europe-wide community of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, and the development of a standardized set of resources could promote and enhance landscape-scale ecosystem restoration.

Introduction

Given the scale of the twin biodiversity and climate crises, urgent action is needed to reverse declines and restore nature and ecosystem processes at large scales. This need is enshrined in the restoration targets of recent international legislation and conventions (CBD 2010, 2022; UN 2015) and the European Union's legally binding Nature Restoration Law (NRL) has brought this issue to the fore for governments in Europe (European Parliament 2023; Hering et al. 2023). The next 5 years, building up to the 2030 deadline for many of these targets, are critical, and achieving these ambitions will only be possible with a step-change in the extent and effectiveness of ecosystem restoration (Murcia et al. 2016). Landscape-scale restoration has a crucial role in meeting obligations and providing vital benefits to biodiversity, climate, and people.

Landscapes can be defined as large, heterogeneous mosaics of natural and/or human-modified ecosystems, often with a characteristic configuration of topography, vegetation, land use, and settlements influenced by the ecological, historical, economic, and cultural processes and activities of the area (Landscapes for People, Food and Nature 2016). Landscape restoration refers to the restoration of biodiversity, natural processes, and sustainable human activities within degraded lands and seas on a scale that may vary from a few square kilometers to ecological corridors that traverse continents (Ockendon et al. 2018).

There are significant advantages of restoring ecosystems at scale. It may be simpler and more cost-effective to focus efforts across one large area than the same area of land spread across many smaller sites. Recovery of natural processes, such as connectivity and hydrological dynamics, is essential to enhance the delivery of ecosystem services and the resilience of ecosystems to future shocks, including climate change, but this requires restoration across a range of scales up to the landscape level (Le Provost et al. 2023). Moreover, people are an integral part of European landscapes and central to their recovery; restoring degraded habitats and species populations across large areas is inspiring and can help win support among local communities and beyond (Gutierrez et al. 2022).

However, there are significant challenges and knowledge gaps related to landscape restoration, due to its relative novelty and the social and ecological complexity of working at scale (Ockendon et al. 2018).

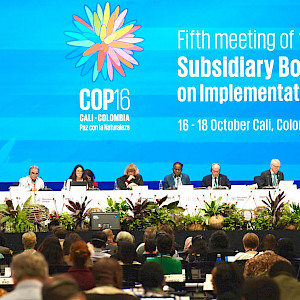

Given the current imperative to restore ecosystems at a landscape scale, a dedicated session was organized at the Society for Ecological Restoration's (SER) European Conference in August 2024, with approximately 50 participants from academia, policy, and practice across Europe. Discussions focused on five key themes with particular relevance to working at landscape scales. This synthesis summarizes the priority barriers and opportunities identified under each theme, providing a summary of current challenges and future directions to enable the scaling up of ecosystem restoration in Europe.

Implementing Restoration at Landscape Scale

Challenges

In the past, landscapes have less frequently been a focus of conservation and restoration. Stakeholders and experts are used to focusing on single habitats, issues, or sites rather than the large-scale recovery of natural processes. This compartmentalization is often reinforced by site-, species-, or habitat-based conservation targets and siloed government departments.

This separation is compounded by the “project-level” approach common in restoration. This typically involves a short project design phase, that hardly gives the time and resources needed to bring together the diversity of individuals, organizations, disciplines, and sectors that have a stake in a landscape. The range of organizations involved in restoration delivery, each with its own methods and processes, also adds delays and complexity, particularly when working across national borders (Mañas-Navarro et al. 2023). After implementation, the time taken to see the effects of restoration actions on landscape-scale processes can be hard to reconcile with project-based expectations of impact (Hodge & Adams 2016). The resources and time needed for sustained long-term, large-scale consultation, planning, implementation, and monitoring are rarely available, jeopardizing the legacy of restoration actions.

Opportunities

National and supranational institutions, including the EU, have a role in providing top-down incentives to work across silos and scales by directing funds and setting targets focused on the recovery of processes rather than habitats and species. Such a shift in focus could also enhance socio-economic impacts and improve coordination and administrative efficiency. Simultaneously, working from the bottom-up, engaging stakeholders, including practitioners, statutory organizations, and local communities early in the planning process can enable the agreement of a common vision, bringing down barriers and guiding the design and implementation of successful landscape-scale projects.

Funders and practitioners can shift thinking away from individual “projects” and commit to restoration in the long term (Hodge & Adams 2016). New financial, governance, and cultural models are emerging that can support the sustained ambition and relationships needed to restore ecosystem function. Examples exist that demonstrate how long-term planning, adaptive management, monitoring, and partnership maintenance can enable landscape restoration (Mola 2024).

Equitable and Effective Stakeholder Engagement for Landscape Restoration

Challenges

The socio-ecological context, variety of land uses, and spatial interactions that define landscapes make stakeholder engagement especially critical but also complex. A key barrier is the difficulty of finding common ground among highly diverse stakeholders with varying backgrounds, needs, and priorities (Cortina-Segarra et al. 2021). The very definition of “landscape”, including its boundaries, spatial flows, and baseline conditions, is often complicated due to its inherently dynamic and socially constructed nature. Poor communication and siloed approaches can create misunderstandings and conflicts (Mañas-Navarro et al. 2023), especially in multi-sectoral landscapes, where concerns about loss of economic stability and livelihoods may weigh against restoration efforts.

Landscape restoration projects frequently operate within diverse political and administrative systems that may not align with restoration goals. Additionally, governments can be slow to address community needs, and legal and technical constraints can hinder collaboration (Bell-James et al. 2023).

Opportunities

Integrating social considerations and structures, incorporating local visions and values, addressing cultural identities, and mapping stakeholders are key steps for successful stakeholder engagement in landscape restoration (Lofqvist et al. 2022). Building consensus around a common vision is crucial, and using visuals, symbols, and inclusive language can help foster emotional connections to restoration goals. Highlighting examples of successful landscape-scale participation can further cultivate community involvement. By starting with a small group of willing participants, projects can demonstrate early success and build trust, allowing efforts to be gradually scaled up. Experts and facilitators can help stakeholders translate their visions into actionable objectives (Elias et al. 2022).

Co-creation methods, such as Living Labs (Lupp et al. 2020), empower stakeholders by involving them in the design, implementation, and evaluation of solutions, promoting long-term engagement. Adaptive co-restoration encourages continuous learning and adjustment, integrating local knowledge within broader ecological and socio-economic contexts. Establishing collaborative governance structures that facilitate meaningful and fair participation at various scales, including those different from the pre-defined landscape, is also critical (Wiegant et al. 2022).

Developing Nature-Based Economies at Landscape Scale

Challenges

Landscape restoration is inseparable from the lives, economy, culture, and historical connections of people to a place. Over recent decades, many rural parts of Europe have seen declining populations, particularly of working-age people, in response to a lack of jobs, low public investment, and poor services (Leal Filho et al. 2017). In such landscapes, ecosystem restoration can provide benefits to people and nature if wildlife recovery can be linked to the development of a nature-based economy. However, a major barrier to the creation of sustainable local economies is a shortage of entrepreneurial and management skills in the communities and non-govenmental organisations working in these landscapes.

High levels of risk and low rates of return mean that enterprises can struggle to access suitable credit; additionally, the high up-front costs of facilities and equipment may be prohibitive. Access to markets may be difficult due to remoteness; moreover, nature-based enterprises often produce diverse seasonal products at low volume, which may not meet market demands for regular, year-round supply.

Lastly, legislative barriers may present obstacles, with small enterprises unwilling or unable to comply with regulations and associated bureaucracy.

Opportunities

Rural land abandonment can represent a double opportunity for nature restoration: reduced anthropogenic pressure allows ecosystems to recover, providing the basis for a new nature-based economy which then champions further environmental recovery (van Twuijver et al. 2020). Nature-based enterprises can meet increasing consumer interest in products that are organic, fair trade or “wild,” with a story behind them. There is also a growing market for new forms of tourism, with low or positive impact, to under-visited but local destinations. Increasing availability of high-speed internet allows businesses in remote locations to access markets and communicate with customers. Furthermore, bringing individuals together in cooperatives can reduce individual up-front costs, with public administrations having a major role in incentivizing such collaborations.

There is growing interest in social investment, providing accessible finance to enable social enterprises to develop their businesses while enhancing environmental and social impacts.

Unlocking Finance for Landscape Restoration

Challenges

Despite growing awareness of the importance of landscape restoration, attracting funding remains a major challenge (World Bank 2022). Scaling up private investment in restoration relies on public investment and policy support (zu Ermgassen et al. 2025). However, Europe's public spending on biodiversity protection is one of the lowest globally (United Nations Environment Programme 2023). Additionally, most funding for landscape restoration is too short-term to demonstrate transformational change, with funding periods typically lasting 1–5 years but the impacts of restoration often taking decades to be realized. Currently, only 14% of the finance flowing into nature-based solutions (including restoration) comes from private sources (United Nations Environment Programme 2023) and in Europe, this may be only 3% (European Investment Bank 2023).

The challenges of monetizing revenue streams mean that most restoration projects are not attractive to traditional investors such as banks and institutions. In addition, practitioners are generally unaware of private or blended finance mechanisms, in which public money is used to leverage private investment. Thus, the business case for restoration has been difficult to demonstrate. The underuse of existing standards and regulations to guide investments in restoration, the requirements of different standards across jurisdictions, and the lack of standardized frameworks for managing and monitoring restoration present further challenges (World Bank 2022; World Bank 2024).

Opportunities

Strategic collaborations, such as the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration Finance Task Force, are emerging between public, private, and philanthropic sectors to scale up restoration finance. The European Commission is committed to providing guidance and an overview of the financial resources available for the implementation of the NRL.

Blended finance instruments can also help de-risk restoration investments and provide technical assistance to restoration projects. Mandatory environmental compensation for development projects, carbon and biodiversity offsets and credits, insurance (SCOR 2024), payment for ecosystem services, and corporate social responsibility are also helping increase finance for restoration. Meanwhile, working at large scales can reduce high transaction costs borne by small-scale restoration project investors.

Monitoring at Landscape Scale

Challenges

Effective monitoring is critical to build the evidence base demonstrating the outcomes of restoration to audiences including policymakers, funders, and local communities, as well as determining whether project goals are met and enabling adaptive management (Alexander 2013). The multiscale and multidimensional nature of landscape restoration requires monitoring that addresses impacts on ecosystems, processes, and society, and their across-scale interactions. Planning such monitoring is complex and time-consuming, but scientific experts often join projects after funding is secured, meaning they cannot input into early stages.

Identifying and monitoring appropriate control sites that allow accurate attribution of project actions is also particularly difficult at the landscape scale. Furthermore, data collection and assessment rarely follow national and international standards. Instead, individual projects typically select monitoring indicators specific to their initiative or funders (Evju et al. 2020). Large interdisciplinary landscape restoration projects require integrated impact indicators to enable understanding of impacts and trade-offs at interconnected scales and to minimize the risk of bias from focusing on datasets showing positive outcomes (Ghoddousi et al. 2022).

Opportunities

Increasing the time and resources allocated to monitoring large-scale restoration projects would assist in understanding success, learning from experiences, and applying this knowledge when designing subsequent projects. Involving stakeholders as co-designers and evaluators promotes learning and trust, and can facilitate the integration of scientific and local knowledge (Bautista et al. 2017).

The increasing availability and resolution of remotely sensed data, ranging from camera traps and acoustic sensors to drones and satellite sensors, offers cost-efficient approaches to monitoring at different scales (McKenna et al. 2023). New user-friendly methods and platforms that integrate satellite-image time series over large areas, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations SEPAL platform (2025), can enable control site selection and counterfactual analysis to demonstrate restoration impact.

The development and acceptance of an integrated monitoring framework, aligned with the NRL, could enable consistent and holistic monitoring across the range of impacts that would be useful to practitioners and governments. This could be adapted from existing frameworks, such as SER's Standards Tools (2025). Additionally, promoting platforms that host monitoring data that might not otherwise be published could contribute to building the evidence base describing landscape-scale outcomes of restoration.

Conclusions

Significant challenges but also opportunities for scaling up restoration in Europe have been identified, with several topics recurring across the different themes discussed. One frequently identified challenge relates to the necessity of working across organizations, sectors, and disciplines. However, the diversity of stakeholders involved was also seen as a strength of landscape-scale working. Changes to funding processes, to allow the time and resources required to bring people together to openly discuss areas of disagreement and build a common vision, could be transformative. Recognizing and funding the planning stages of landscape restoration projects as a vital basis for success can produce a much stronger final result (e.g. the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme's Planning grants).

The tension that can exist between current legislation and bureaucracy and restoring at landscape scale reflects an inability of existing political and funding systems to enable and incentivize cross-sectoral and cross-scalar working. There is a need to develop integrated, long-term strategies that involve multiple stakeholders and governance levels, alongside sustainable funding mechanisms. Increasing political interest in large-scale restoration, intensified by the NRL in Europe, could provide an opportunity to encourage working beyond individual siloes and sites and to harmonize processes in the long term.

Similarly, there is a need to combine top-down strategies defining guidelines and frameworks to achieve international goals with bottom-up approaches, whereby European, national, and sub-national governments can quickly mobilize to establish financial and administrative mechanisms to promote and facilitate landscape-scale projects. Benefits can be gained from aligning local initiatives with broader international frameworks, like the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD 2022) and the NRL, to demonstrate how landscape restoration contributes to national and regional goals and encourage legal, financial, and political support.

There is significant interest, knowledge, and experience in landscape restoration in Europe, with novel models of landscape-level working, from planning to implementation and monitoring, increasingly being trialed. The development of a community of scientists, practitioners, policymakers, and funders could be valuable in facilitating the exchange of ideas, learnings, know-how, and experiences, with SER-Europe and the BiodivRestore Knowledge Hub (2025) in key roles. We also recognize the value of a well-documented network of standards-based landscape-scale projects to serve as a guide, such as the Living Labs network. Developing and sharing new resources to overcome identified barriers, such as a standardized monitoring framework and tools and platforms that make expert analyses more accessible, is also a priority, potentially facilitated by initiatives developed under SER and the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Scaling up restoration requires integrative thinking across different sectors and disciplines, bridging the gaps between research, policy, and practice. It also demands political pragmatism and compromise to address cultural, governance, and funding challenges. Increasing momentum offers hope that these efforts can be harnessed to deliver an ambitious landscape-scale restoration program across Europe, providing critical benefits for nature and people.

Acknowledgments

We thank everyone that presented and participated in discussions on landscape restoration at SERE2024 and S. Ruysschaert, S. Tom, L. Fletcher, B. Fairburn, R. Cassola, G. Ascenzi, and A. Diaz. N.O., T.S., D.T., and A.B. were funded by Arcadia. S.Bi. is part of MERLIN (https://project-merlin.eu) funded by the H2020 Societal Challenges (grant 101036337). J.C.-S. and S.Ba. are funded by Conselleria de Educació, Cultura, Universitats i Ocupació, Generalitat Valenciana (CIPROM/2021/001). S.Ba. is funded by PID2021-125517OB-I0 MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF A way of making Europe”. J.V.d. was funded by ITC Ingenuity Space4Restoration and NWO (OSF23.2.091).