With legally binding targets now in place under the EU Nature Restoration Regulation, and a global goal to restore 30 percent of degraded ecosystems by 2030, large-scale restoration is rising up the political agenda. Across Europe, there is growing recognition that to meet the scale of this ambition, fragmented or degraded ecosystems cannot be effectively restored one site at a time.

However, scaling up is far from simple. It demands new ways of working, longer timeframes and greater collaboration across sectors. There are also a number of challenges that can limit progress: for example, how restoration is funded, how local voices are involved, and how knowledge is built and shared.

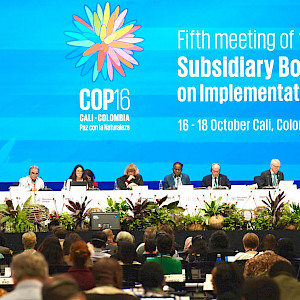

These challenges, and possible solutions to them, have now been explored further in a new article, co-authored by UNEP-WCMC, which grew from a symposium that took place during the 2024 Society for Ecological Restoration Europe conference. UNEP-WCMC took part in the event through its Convening for Restoration project, which is funded by the Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme and brings together experts and stakeholders from across science, policy, finance and practice.

Funding that fits the task

Finance remains a major barrier to restoration. Most projects rely on short-term public funding that does not match the long timescales involved. Meanwhile, private investment is limited, partly because returns are often uncertain or slow to appear.

One of the main barriers faced by almost all restoration projects is access to adequate long-term funding. Most funding cycles are one to five years, which is too short to demonstrate the impact of restoration on ecosystems. There is a need for a change in attitude towards restoration finance, to give the breathing space for projects to reach their full potential

(Anushree Bhattacharjee, Lead, Restoration for Sustainable Development, UNEP-WCMC, and article co-author).

There is growing interest in alternative finance models. Blended finance, biodiversity credits and payments for ecosystem services are being explored, although many practitioners still lack access to advice or support, particularly for private finance options. To address this gap, UNEP-WCMC has convened an expert Finance for Restoration Taskforce and will soon be releasing private finance guidance specifically aimed at restoration project developers in Europe. While the guidance is focussed on continental Europe, many of its insights will be globally relevant.

One clear message from the symposium was the importance of investing in the planning phase. When coordination is supported from the outset, and key stakeholders are able to focus on long-term financial planning, restoration partnerships are more likely to take root and deliver sustained impact.

Who gets a say, and when?

Restoration at the scale of landscapes inevitably affects a wide range of people and land uses. Projects that do not create space for meaningful engagement with local stakeholders risk overlooking regional priorities or repeating past mistakes. While consultation is often included, it may be too narrow, too late or too disconnected from decision-making.

Where engagement is secured early on in a project and sustained throughout, this builds trust and aligns goals. Approaches such as Living Labs and participatory design offer practical ways to involve people in shaping restoration activities. These methods take time and resources, but they help ensure that restoration efforts are better understood, more locally relevant and more likely to endure.

Gaps in knowledge, not just nature

Many landscape-scale projects still face uncertainty when it comes to planning and tracking progress. The complexity of working at this scale is often not matched by the tools or support available. Short-term project models leave little room for early-stage collaboration or long-term learning.

"Monitoring remains a particular challenge in large-scale restoration. It is often introduced too late, underfunded, or developed without shared standards, which makes it hard to assess outcomes or compare projects. But now we’re seeing more interest in better tools and approaches that work well over the long timescales and large areas involved, for example satellite data to participatory monitoring methods" (Dr Nancy Ockendon, Science Manager, Endangered Landscapes & Seascapes Programme, and article co-author)

There is growing interest in developing an integrated monitoring framework that can support consistent and holistic assessment of restoration outcomes. While the Nature Restoration Regulation calls for progress to be measured, it leaves the details largely undefined. A shared framework could help fill this gap and enable better coordination across projects. Existing tools, such as the Society for Ecological Restoration’s Standards-based approach, offer a potential foundation that could be adapted to suit European needs. Improving access to monitoring data, particularly results that might otherwise remain unpublished, would also help build a stronger evidence base and support learning across different landscapes.

Moving forward

Restoring ecosystems at landscape scale can deliver substantial benefits for biodiversity, climate and communities. But to succeed, it requires strong foundations. This means funding models that reflect the realities of long-term change, better tools for planning and monitoring and more inclusive ways of working.

The experiences shared at the symposium underline the need for continued exchange across projects, countries and disciplines. By learning from one another and addressing common barriers, Europe’s restoration community can help turn policy ambition into meaningful outcomes on the ground.

For a deeper look at the discussions behind these insights, including practical examples and references, read the full article published in the journal RestorationEcology.